“On Retirement Income” series:

- A 4% Rule Fable

- The 4% Rule Launches a Bigger Discussion

- From Mindless Inconsistency to Mindless Consistency

- Stock/Bond Portfolios and Sequence-of-Returns Risk

- Goals-Based Investing Starts with Goals

- Guaranteed Income Sources (Social Security, Etc.)

- How Guaranteed is Guaranteed Income?

- Get Real Income by Getting TIPSy

- TIPS Q&A

- More to come…

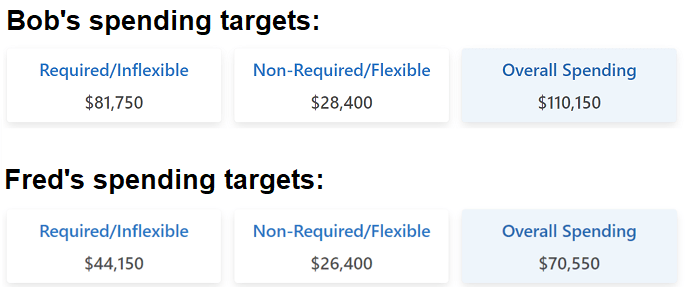

In the prior installment in this series, our fictional twins Bob and Fred constructed annual retirement budgets, wherein each spending line item was labeled as an “inflexible” or a “flexible” expense. The resulting, rolled-up annual expenses for the two brothers look like this:

In constructing a “Layer Cake” retirement investment plan for our clients, the first order of business is to secure safe income to cover the required/inflexible spending needs uncovered in the budgeting process. This is why “Layer 1” is the foundational stratum of the Layer Cake.

“Layer 1” Income Sources: Social Security/Pensions/Annuities

Layer 1 of our Layer Cake system consists of contractually guaranteed sources of income. People don’t often think of these income sources as personal assets. Yet they are often some of the most valuable assets carried into retirement. This is true in a literal sense, as “present value” calculations can demonstrate. It is also true in a more figurative sense, because “how much income can this asset produce?” is often a more meaningful question in retirement than “what is this asset worth?” Guaranteed income sources provide an explicit answer to the former question, whereas an investment portfolio can answer only the latter question unambiguously.

(Side note: The value of guaranteed income is also contingent on the credibility of the guarantor. We will open that can of worms in the next article.)

One of the key elements of our “true goals-based investing” process is to match required/inflexible annual expenses with contractually guaranteed, non-volatile income sources, such as the following:

- Social Security: This is the largest source of guaranteed income for most retirees. In fact, for many retirees, Social Security is their largest single asset.

- As an added benefit, Social Security payments are adjusted yearly to keep pace with a broad measure of inflation called the Consumer Price Index (CPI).[1] This can be an extremely valuable benefit. As time passes, the magnitude of the “required” expenses[2] in Bob’s and Fred’s budgets (and yours and mine as well) is likely to increase due to inflation, which is the tendency over time for a dollar’s buying power to decline. The CPI adjustments in Social Security are designed to offset these increases.[3]

- Pensions: Erstwhile employees of government entities often have public sector pensions, which can complement or replace (or to some extent compete with) Social Security. Rapidly retreating into myth and yore is the private sector corporate pension, a wondrous employment perk the cost of which relatively few companies remain willing to bear. Congrats to those who have one!

- Note, however, that inflation adjustments rarely accompany corporate pension income. Public sector pensions more commonly have “Cost of Living Adjustments” (COLAs), though such COLAs are often capped or otherwise limited, reducing inflation protection when inflation is at its worst.

- Annuities: The term “annuity” can invoke a broad range of products (especially to annuity salespeople), but here we speak primarily of those simple contracts that offer guaranteed monthly/quarterly/yearly income for a specified timeframe, or for the life of the annuitant(s).

- Here again, few such contracts come with COLAs, partly because the money illusion impels annuity buyers to reject them, and partly because no annuity provider at present offers true inflation protection in the form of CPI-linked payouts (a fact about which we at Round Table have definite opinions).

- [Bonus income source] Employment: While not typically contractually guaranteed, continued employment can be an excellent source of additional income in retirement. This can look like part-time work for a previous employer, freelance self-employment, or even a shift into that other career that was always of interest but less remunerative.

Okay, back to Bob and Fred.

Fred’s Social Security

Fred turns 65 this year, and his initial plan was to file for Social Security now, so that he can collect checks throughout his retirement. He knows he could get a higher monthly income by waiting to file, but he figures the depletion of his investment assets to cover his living expenses in the meantime would be too egregious a cost to incur.

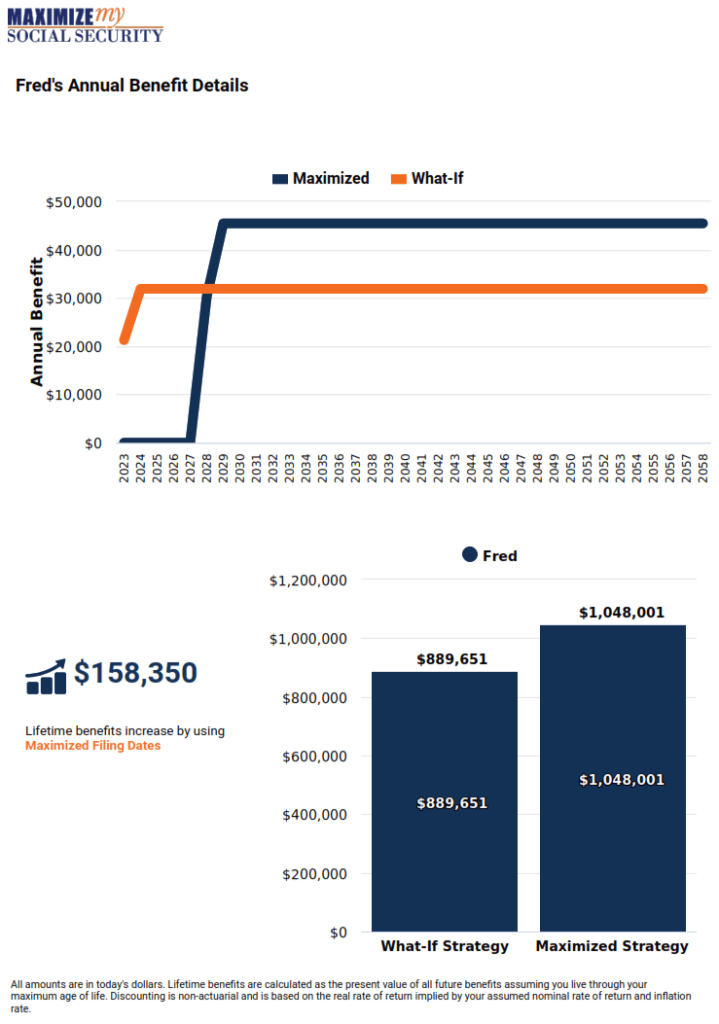

However, with the help of one of our favorite software systems, Maximize My Social Security, we make a recommendation to Fred that we suggest very commonly: The 8% annual increase in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) income from delaying Social Security benefits means waiting to claim until age 70 is often one of the best retirement income decisions someone can make.

Details from the Maximize system are shown below. By waiting until age 70, Fred would increase his annual, inflation-adjusted, Social Security payments from about $32,000/year to about $45,500/year. This could potentially create $250,000+ in additional lifetime income. (Running a present value calculation, the software determines that this is equivalent to creating over $158,000 in asset value today.)

“Sure,” says Fred, “that’s what it looks like if I live to 100, but what if I die before the higher yearly income has made up for what I’m giving up in these first five years?”

Our response? “Well, in that case you’ll be dead, so you won’t be worried about what you missed out on.” No wait, that’s not it…hang on a second…oh yeah, I remember…

Our response? Paradoxically, not taking Social Security for the next five years will allow Fred to spend more money, not less, even over the next five years, with the same factor of safety.

This occurs because a well-designed, goals-based investment plan must account for “longevity risk”[4]—i.e., don’t let someone’s income fall off a cliff if they experience unusual longevity. This consideration generates the following waterfall effect:

- Social Security is the single best tool for managing the two-headed monster of longevity risk and inflation risk.[5]

- Consequently, maximizing Social Security’s payout by delaying to age 70 is the single best method of hedging that risk.

- This, in turn, frees up more of a retiree’s other assets. So much so, in fact, that even though you must pull more from those assets prior to age 70, this is more than offset by how much less you rely on other assets after age 70.

We can even model out for Fred just how much more income he can take starting today by delaying Social Security to age 70. But for that, we’ll need to move higher up the layers of the Layer Cake. Stay tuned!

Note that once Fred starts claiming at age 70, his Social Security payments should be adequate to cover his required/inflexible annual spending needs of about $44,000/year. But in recommending he delay filing, we ideally want to create a secure, inflation-protected income “bridge” for about four years (from his retirement next year to the time he turns 70) to replace the ~$45,500/year he will start to receive at 70. How do we accomplish this? Again, stay tuned! (Or…take a deep dive into our preferred methodology here.)

Bob’s (and Barbi’s) Social Security, etc.

Because they are fictional clients and we can make whatever changes we think are interesting, it suddenly turns out Bob has a wife, Barbi, who has been the primary breadwinner of their family.[6]

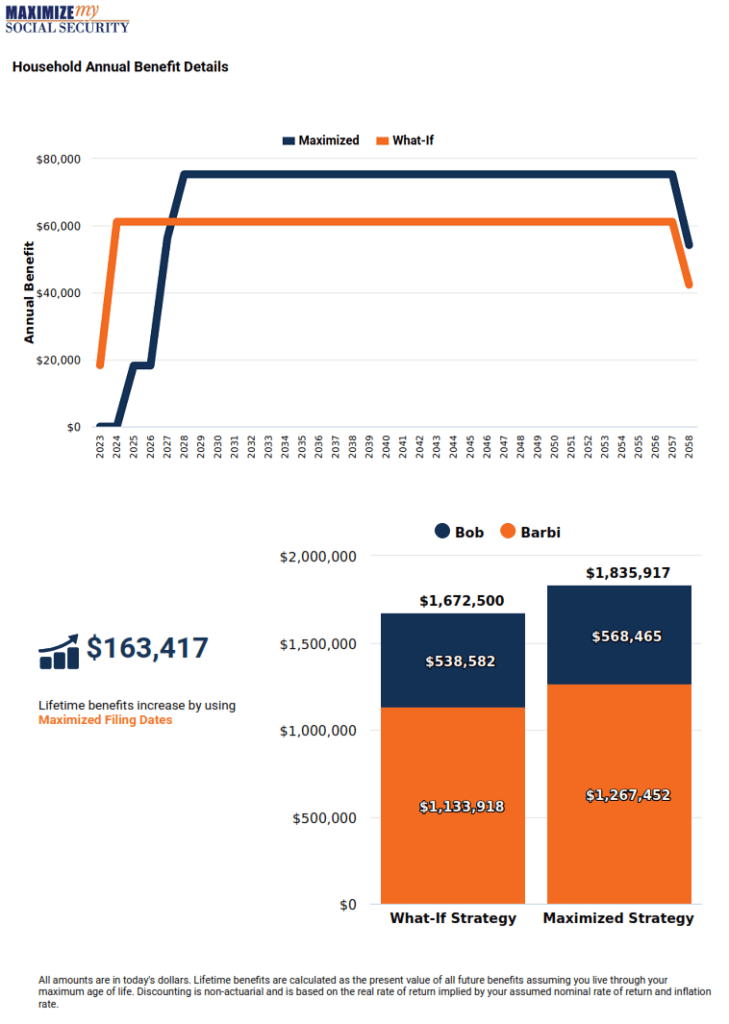

Again, we optimize their Social Security claiming decision, comparing the optimal choice to a bogey of immediately filing this year (Bob is 65 and Barbi is 66). Again, we conclude it would be best to file at age 70…but only for Barbi. A couple wrinkles imply that Bob would be better off filing at his “full retirement age” (FRA) which is in 2024, when he turns 66 and 8 months:

- Wrinkle 1: Bob’s spousal benefit will be somewhat larger than his own benefit. However, whereas a filer’s own benefits max out with an age 70 filing, spousal benefits max out at full retirement age…provided the spouse in question has also filed at FRA or later.

- Wrinkle 2: Because Barbi is waiting to file until 2027, Bob cannot claim a spousal benefit until then. But he does have a Social Security benefit of his own, which he can claim at his FRA (in 2024) without reducing his spousal benefit when it kicks in in 2027.

Here’s what this looks like:[7]

I realize this all sounds complicated, but…well, yeah, actually it is pretty complicated. Social Security maximization can run the gamut from super simple (like Fred’s situation) to far more complex than even Bob and Barbi’s recommendation.[8]

A comprehensive analysis of all permutations is far beyond the scope of this article. But a comprehensive analysis of how to optimize our clients’ Social Security claiming decisions is well within the scope of what we do at Round Table!

Bob tells us that they were planning to wait until age 70 anyway (though he appreciates our pointing out that he should file sooner!), because they conveniently happen to have five years remaining on a $78,000/year fixed annuity through Deus ex Machina Insurers. So unlike Fred, Bob doesn’t need us to build an “income bridge” to Social Security.

However, Bob and Barbi have a different issue. Whereas Fred’s Social Security payments—once they kick in—will be sufficient to cover the required/inflexible expenses in his budget, Bob/Barbi’s SS combined payment of about $75k/year falls short of their nearly $82k required/inflexible spending needs. In other words:

- Fred has a large gap in his guaranteed income—the entire inflexible expense amount—but only for the first four years of his retirement.

- Bob and Barbi, on the other hand, have a small gap—around $7000/year, plus inflation—but for the rest of their lives.

Again, we’ll see the solution in a later article.[9] And of course, both Bob and Fred have flexible expenses in their budgets as well. We’ll get to that too, as we continue to bake their Layer Cakes as this series rolls along.

[1] Technically, Social Security payments are linked to a measure called the Consumer Price Index for Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). While this differs slightly from the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) to which the inflation adjustments on TIPS and I-Bonds are tied, the distinction is likely to be too small to have a material impact on outcomes. (See also footnote 3.)

[2] “Non-required”/“flexible” expenses can also experience inflation, of course, but there are a couple mitigating factors: (A) The ability to be flexible with these expenses can create flexibility around the method for generating the income to meet the expenses, reducing the need for expensive, contractually guaranteed, CPI adjustments. (B) Spending on travel/entertainment/hobby line items that make up a sizable chunk of the flexible expense category will often decline over time, due to retirees’ lives slowing down as they age; this decline in consumption may (wholly or partially) offset inflation in the cost of such items.

[3] Granted, no broad measure of inflation will perfectly match any individual’s personal inflation experience, due to differences arising from the individual’s consumption basket, geography, etc. Nonetheless, to a first approximation, it can at least be stated with confidence that if the inflation faced by an individual is high, CPI-measured inflation will be high, and vice versa. The inflation hedge is imperfect, but it is a true hedge nonetheless.

[4] If someone has a terminal medical diagnosis, a free-solo rock-climbing addiction, or other objectively plausible reason to expect lower-than-average longevity (and no spouse reliant on continuing their benefits), then it can make sense to claim benefits earlier. But otherwise, be aware that (A) healthy people have a pronounced tendency to underestimate their life expectancy, and (B) as retirement expert Wade Pfau puts it, people should “play the long game” anyway, planning for the possibility that they outlive their life expectancy. We believe most people would agree that outliving their income is a far worse financial risk than dying with unspent assets.

[5] To understand why these are related, note that the “deep longevity” years are also the timeframe wherein cumulative inflation is most erosive to the buying power of level nominal payments.

[6] Admittedly my original idea was to use Bob and Fred in just one article. We didn’t do as much planning ahead with this article series as we do with our clients’ retirements!

[7] Notably the income in Bob and Barbi’s chart declines in 2058. This is because the scenario analysis assumes both folks live to age 100. Because she is one year older, Barbi passes one year earlier, at which point Bob stops taking his spousal benefit and receives Barbi’s income as a survivor benefit instead.

[8] And we haven’t even discussed tax complications yet!

[9] Or, again, see (most of) the solution in this article.

DISCLOSURES: All content is provided solely for informational purposes and should not be considered an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Round Table Investment Strategies (Round Table) does not offer specific investment recommendations in this presentation. This article should not be considered a comprehensive review or analysis of the topics discussed in the article. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Despite efforts to be accurate and current, this article may contain out-of-date information, Round Table will not be under an obligation to advise of any subsequent changes related to the topics discussed in this article. Round Table is not an attorney or accountant and does not provide legal, tax or accounting advice. This article is impersonal and does not take into account individual circumstances. Reading this article does not create a client relationship with Round Table. An individual should not make personal financial or investment decisions based solely upon this article. This article is not a substitute for or the same as a consultation with an investment adviser in a one-on-one context whereby all the facts of the individual’s situation can be considered in their entirety and the investment adviser can provide individualized investment advice or a customized financial plan.

The data shown in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as an investment recommendation or strategy, or as an offer to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. While the sources of data included in any charts/graphs/calculations are believed to be reliable, Round Table cannot guarantee their accuracy.