“On Retirement Income” series:

- A 4% Rule Fable

- The 4% Rule Launches a Bigger Discussion

- From Mindless Inconsistency to Mindless Consistency

- Stock/Bond Portfolios and Sequence-of-Returns Risk

- Goals-Based Investing Starts with Goals

- Guaranteed Income Sources (Social Security, Etc.)

- How Guaranteed is Guaranteed Income?

- Get Real Income by Getting TIPSy

- More to come…

Total Return Income Strategy Q&A

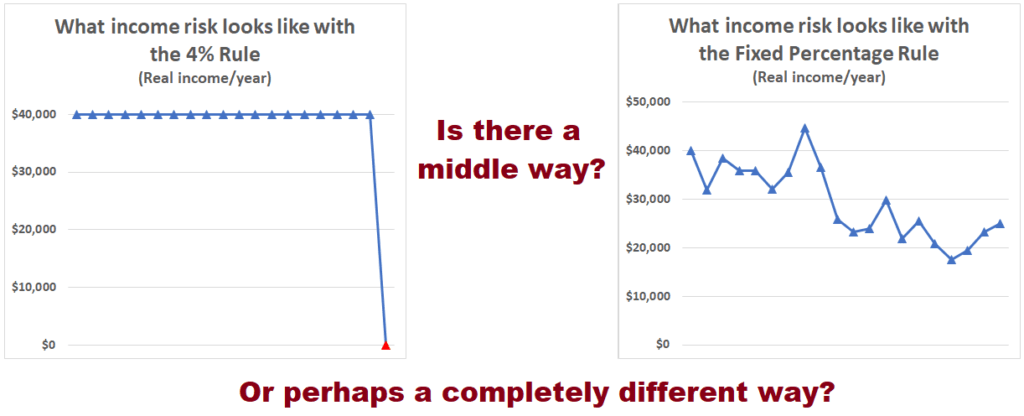

Our friends Bob and Fred have now been introduced to two retirement portfolio withdrawal rules on opposite ends of a spectrum:

- The 4% Rule, espoused by Rule of Thumb Investment Advisors (ROT IA), starts by withdrawing 4% of initial portfolio value, and continues to draw the same dollar amount, with annual adjustments for inflation, every year until retirement ends[1]…or until money runs out, in which case income collapses to $0.

- The Fixed Percentage Rule, advocated by Supremely Consistent Asset Managers (…), withdraws the same percentage of the remaining asset base every year, thus varying income proportionally with portfolio performance.

This article consists of a Q&A-style elucidation of the nature of the risks on the opposite ends of this “total return strategy”[2] spectrum. In our next few articles, we’ll explore retirement income sources that exist off this spectrum altogether.

Disclaimer: This article—or at least the sequence-of-returns section—may be the most technical of all articles we will publish in this series. Feel free to skip this one! The lessons learned by Bob and Fred in the last article are sufficient for what comes next.

If the 4% Rule and Fixed Percentage Rule are polar opposites, how can they both be risky?

For both strategies, the risk derives from the volatility of the assets in the portfolio from which the withdrawals are made. In our article on TIPS vs. I-Bonds, we noted that marketable securities can be risk-free either in present value terms or in future income terms, but not both.

However, while a portfolio can’t be safe in both senses, it can be safe in neither sense! A portfolio of stocks and bonds[3] is just such a creature, producing neither secure asset value (the value of the portfolio can go down) nor safe income (the amount of income the portfolio is capable of producing can decline). The choice between the 4% Rule, the Fixed Percentage Rule, or anything in between merely elects how we wish that risk to manifest: as “tail risk”/“cliff risk” (4% Rule), as income volatility (FP Rule), or some of both, as illustrated by this chart from the previous article:

If a stock/bond portfolio can’t give me safe asset value or safe income, why would I want it?

Not all risks come with higher expected returns, but stock/bond[4] market risk does! Relative to a risk-free asset (e.g., cash[5], T-Bills) or income (e.g., TIPS ladders, SPIAs/DIAs) approach, the stock/bond risk premium can enable an investor to obtain significantly higher income and/or significantly higher terminal wealth—the remaining asset value when your retirement terminates[6]—on average and in most cases, in exchange for the smaller but certainly not negligible possibility of an income shortfall or premature exhaustion of assets.

(Side note: While the “cliff risk” of suddenly going to $0 might be the scariest aspect of the 4% Rule, perhaps an even great inefficiency is the fact that the fixed withdrawals mean you can die with a massive amount of unspent wealth, if the markets perform extremely well. Note that the Fixed Percentage Rule eliminates this risk as well, allowing income to skyrocket if the portfolio does.)

Hmm…So when is that tradeoff worthwhile?

Much of this series will be devoted to that question, but for now we’ll just say that it’s a matter of risk tolerance and risk capacity:

Risk tolerance refers to an investor’s ability to stomach the ups and downs of the market and willingness to accept the possibility of lower income and wealth in exchange for the probability of higher income and wealth.

Risk capacity refers to the amount of risk an investor is theoretically able to take, e.g., before the potential downsides threaten non-negotiable goals. At Round Table, we view required/inflexible income needs (to cover fixed/non-negotiable spending costs) as the most fundamental such goal, which is why our Layer Cake retirement investment model takes a “safety-first” approach, seeking to match such expenses with secure income in retirement, before supplementing with the risky but higher-on-average income attainable from stocks and bonds.

Hey, the title of this article includes “Sequence-of-Returns Risk,” but you haven’t mentioned it yet. What does that mean, anyway?

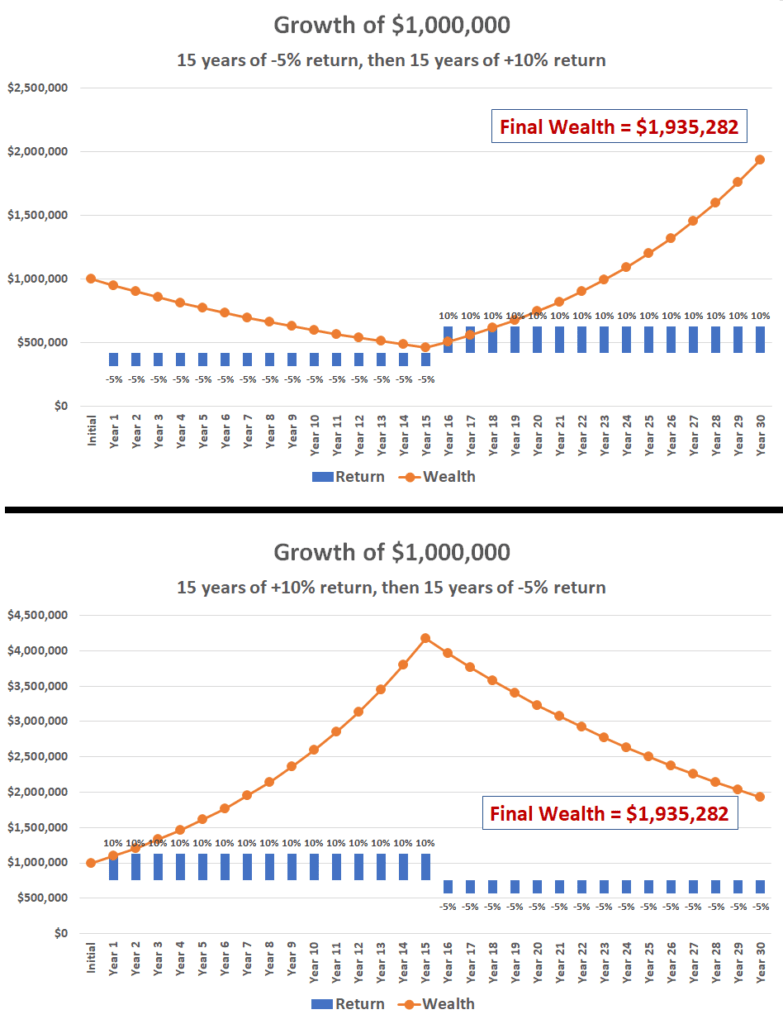

Oh yeah, thanks for the reminder![7] The term “stock/bond risk” most commonly refers to the volatility (or max drawdown, or downside semivariance, or…) of a stock/bond portfolio over time. Thus, the “riskiness” refers to the fact that investment returns will vary over time (in case you hadn’t noticed), which in turn can lead to a wide dispersion of potential long-run returns.

However, under this formulation, the precise order of returns does not matter. As an unrealistic but mathematically simple example, 15 years of +10% returns followed by 15 years of -5% returns produces the exact same 30-year end-to-end return (~94%) as does 15 years at -5% followed by 15 years at +10%.

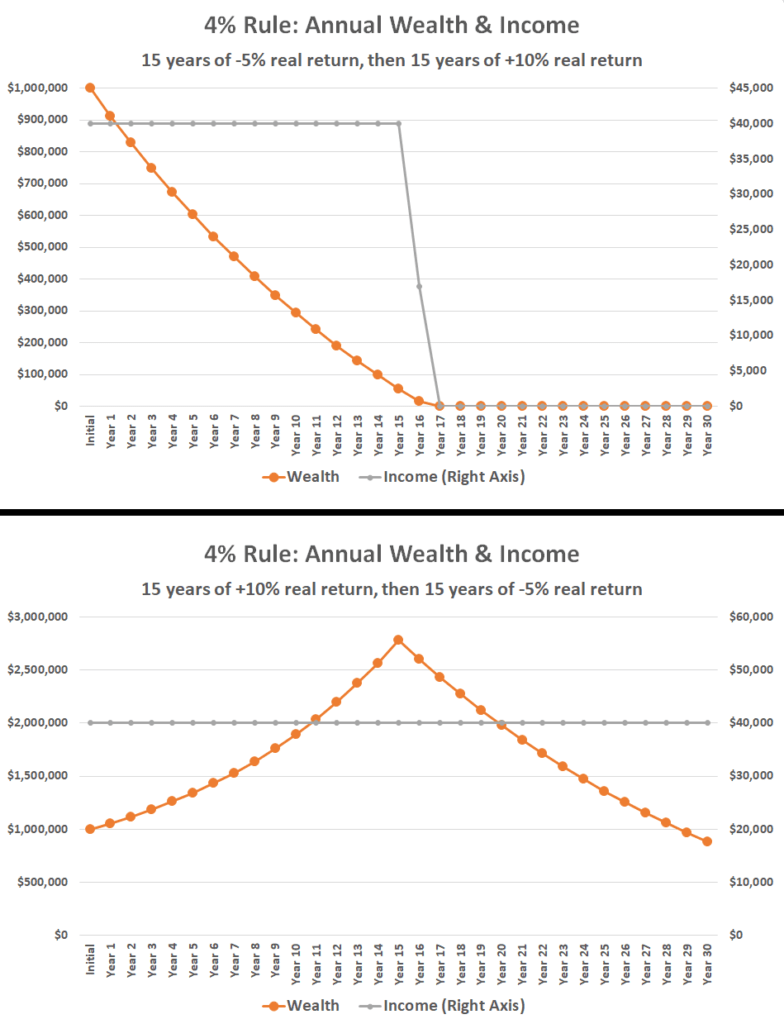

But once you plan to pull withdrawals from a portfolio to produce retirement income, the sequence of returns becomes quite important! For example (and assuming real returns[8] net of fees and expenses), under the 4% rule:

- The first sequence (-5% for 15 years, then +10% for 15 years) produces $40,000/year in real income upfront and for 15 years, followed by a swift collapse to no wealth and no income.

- The reverse sequence (+10% for 15 years, then -5% for 15 years) produces $40,000/year in real income all the way through Year 30, with nearly $870,000 (inflation-adjusted) dollars remaining at the end.

In other words, when you retire, you ideally want to get all the good returns first and all the bad returns later. But per the unassailable Jagger Rule of investing, you can’t always get what you want…and hence this problem is known as “Sequence-of-Returns Risk.”

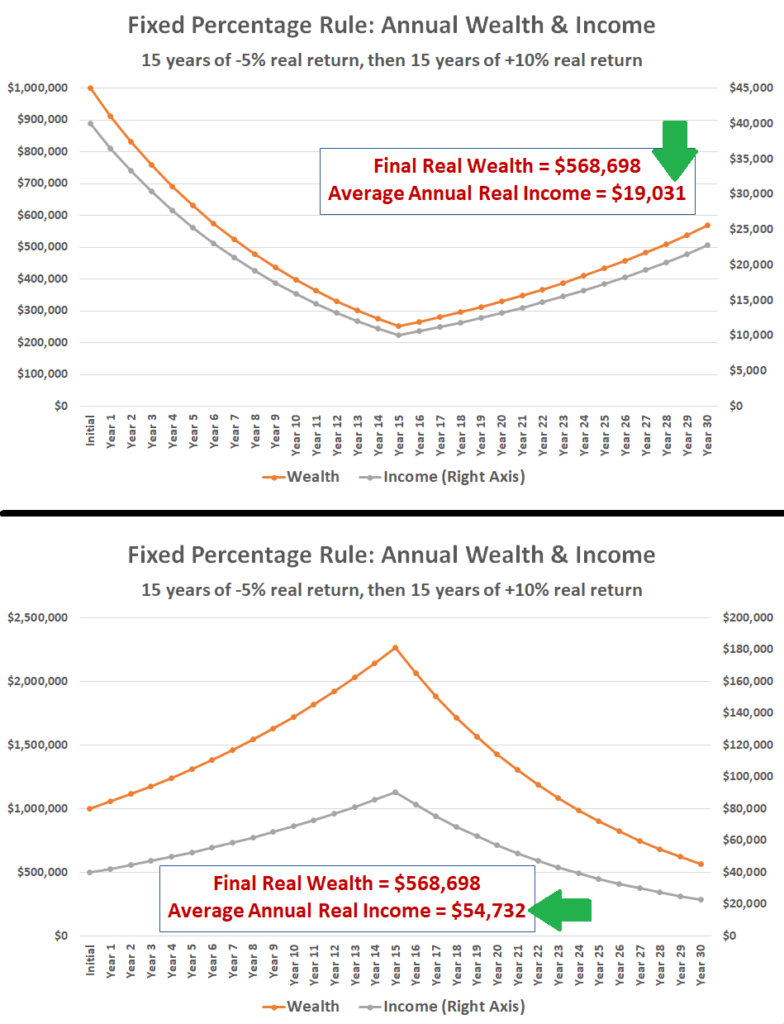

Does the Fixed Percentage Rule have sequence-of-returns risk as well?

The correct answer is yes. The politically correct answer is it depends who you ask. SoR Risk is commonly defined as the risk of running out of money in retirement. And as noted in Bob and Fred’s last adventure, the Fixed Percentage Rule prevents retirees from ever running out of money completely.[9] Moreover, the FP Rule even eliminates SoR Risk in a slightly more expansive sense: I.e., terminal wealth will be the same no matter the order of returns.

But other than “more than zero,” there’s really no additional limit to how low income and wealth can get with the FP Rule. So we ask you: Does the difference between the two outcomes below look like “no sequence-of-returns risk” to you?

Insofar as averaging more income is, shall we say, better than averaging less income, we would submit that sequence-of-returns risk most certainly exists with the Fixed Percentage Rule as well as the 4% Rule. The real difference is that both run-of-the-mill stock/bond risk and sequence-of-returns risk manifest:

- As “tail risk” or “cliff risk” (i.e., risk of sudden ruin) in the 4% Rule, and

- As income volatility in the Fixed Percentage Rule

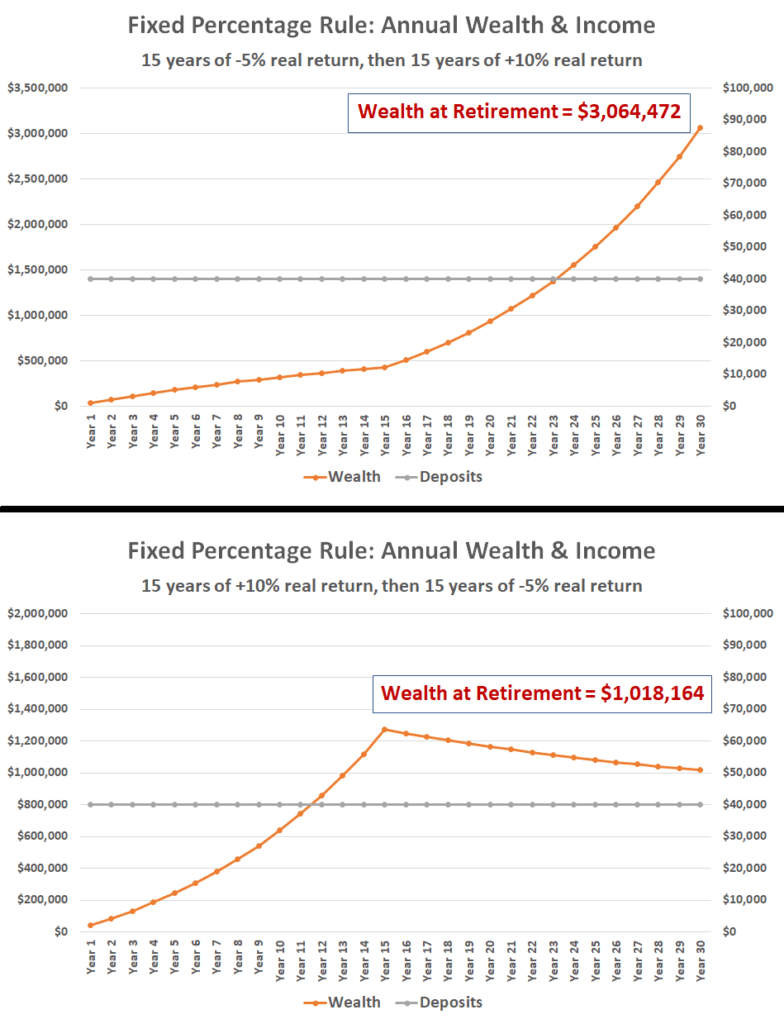

Okay, but sequence-of-returns risk exists only in retirement, once I start taking withdrawals, correct?

Alas, this is an all-too-common misconception, leading to an overly broad-brush distinction between the “accumulation” and “decumulation” phases of the investment lifecycle.

Consider this example, in which someone experiences the same two returns sequences for 30 years prior to retirement, while saving $40,000/year:

Two things to notice:

- Clearly the sequence of returns matters a great deal pre-retirement as well!

- The preferred pattern pre-retirement is the opposite that in retirement: During accumulation, ideally all the bad returns happen at the beginning and all the good returns happen at the end.

A different way of phrasing this mirroring of preference is the following: Sensitivity to stock/bond market risk is highest in the years nearest retirement—both before and after—and declines the further you move away from retirement—either younger or (counterintuitively) older.

We will revisit this surprising revelation later in this series. But in the meantime, feel free to skip straight to contacting us to see how we can put all this knowledge to work in designing a retirement investment plan for you!

[1] How’s that for a pleasant euphemism? A different euphemism: Until you croak!

[2] “Total return strategy” refers to any type of retirement income/withdrawal strategy that generates cash flow for retirement spending from a portfolio of stocks, bonds, and other volatile assets.

[3] I am assuming here that the bond portfolio is not laddered or duration-matched Treasury exposure.

[4] In general, we view the bond portion of a stock/bond portfolio as primarily a risk reduction mechanism, and the stock portion as the return premium mechanism. Nonetheless, at least insofar as the bonds include some credit risk, they too have an expected risk premium above risk-free securities.

[5] The irony doesn’t escape me of speaking of “cash” as risk-free in an environment where the most common form of “cash”—bank accounts—has been under an unusual degree of pressure and scrutiny. But if your bank deposits are below the $250,000 FDIC maximum, it really can’t get much safer than that. (And it now appears the safety of higher balances may not be far behind.)

[6] Again, a pleasant euphemism. Another euphemism: When you kick the bucket!

[7] Readers dismissing this exchange as a corny joke neglect the possibility that I’ve merely herein transcribed my own stream-of-consciousness internal dialogue.

[8] Which is to say, the return above/below the annual inflation rate, since the 4% Rule adjusts for inflation.

[9] Again, barring, y’know…

DISCLOSURES: All content is provided solely for informational purposes and should not be considered an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Round Table Investment Strategies (Round Table) does not offer specific investment recommendations in this presentation. This article should not be considered a comprehensive review or analysis of the topics discussed in the article. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Despite efforts to be accurate and current, this article may contain out-of-date information, Round Table will not be under an obligation to advise of any subsequent changes related to the topics discussed in this article. Round Table is not an attorney or accountant and does not provide legal, tax or accounting advice. This article is impersonal and does not take into account individual circumstances. Reading this article does not create a client relationship with Round Table. An individual should not make personal financial or investment decisions based solely upon this article. This article is not a substitute for or the same as a consultation with an investment adviser in a one-on-one context whereby all the facts of the individual’s situation can be considered in their entirety and the investment adviser can provide individualized investment advice or a customized financial plan.

The data shown in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as an investment recommendation or strategy, or as an offer to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. While the sources of data included in any charts/graphs/calculations are believed to be reliable, Round Table cannot guarantee their accuracy.