In the past few months, our articles pointed out a couple curious anomalies:

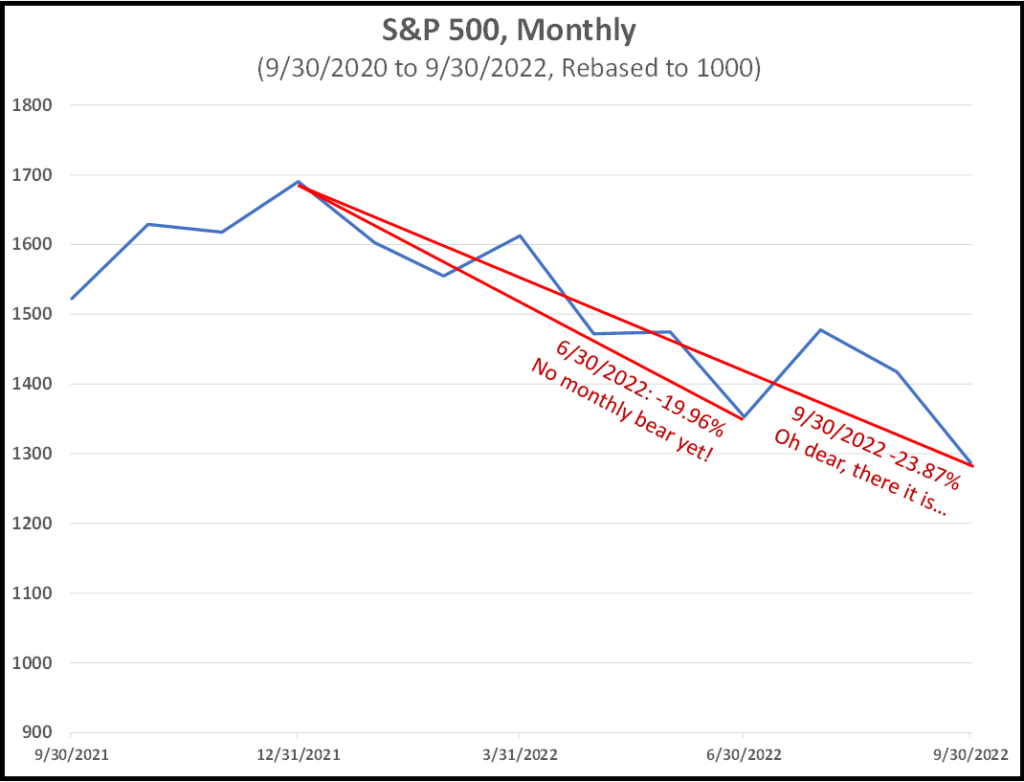

- The current bear market (and the 2020 COVID-induced bear) existed in daily S&P 500 data, but not in monthly data. Reckoning by monthlies, the bull market that began back in March 2009 was ongoing.

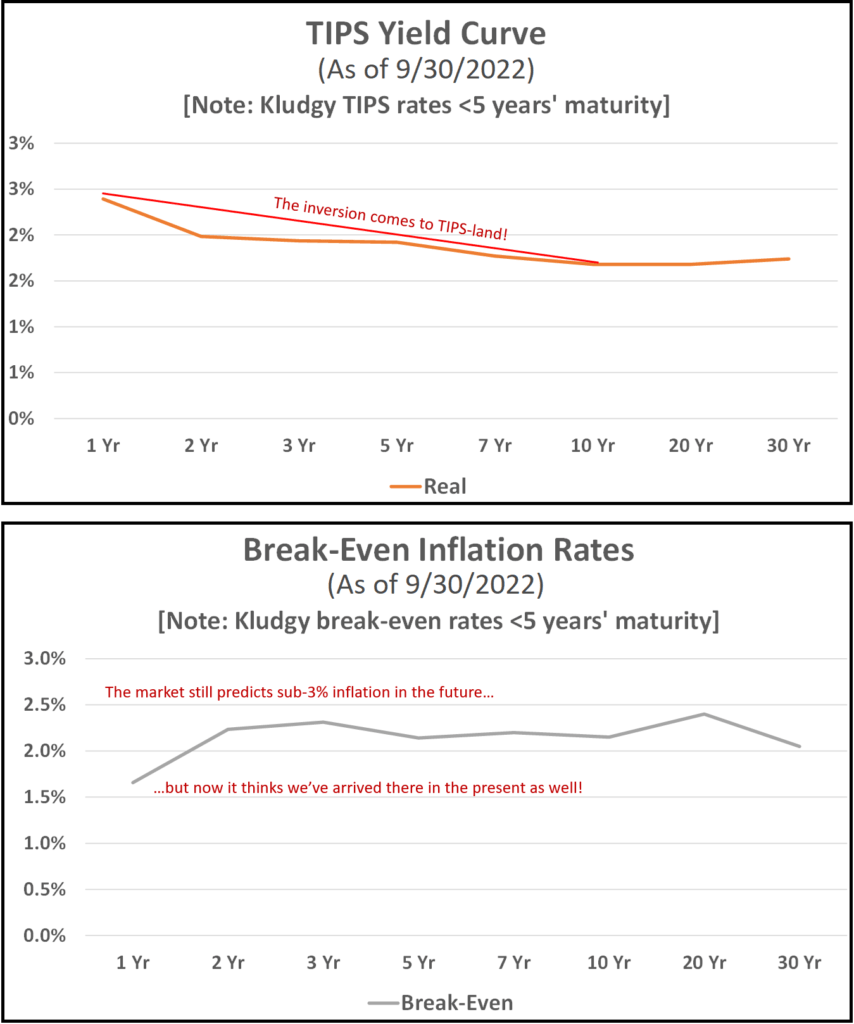

- The current “yield curve inversion” existed in the nominal Treasury curve but not the TIPS (real) curve. In other words, the yield inversion was driven entirely by forward-looking inflation expectations.

Fast-forward a couple months and both anomalies have evaporated…

The Bear is There

When we wrote ”Zoom Out, It’s a Bull. Zoom In, It’s a Bear” on July 1st, the drawdown in monthly S&P 500 total return data was -19.96%—about as close to a bear market as you can come without triggering the tripwire.

At the time, we wrote, “The current drawdown is nowhere near recovery yet, and the tiniest drop for the month of July could push us into bear territory by either definition.” Well July was a big up month instead, but subsequent losses in August and especially September have finally pushed the monthly data into the first bear market since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC).

https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/%5ESP500TR/history?p=%5ESP500TR (data)

The bizarro stats deserve to be memorialized:

- By intraday data, the post-GFC bull market lasted just two years and two months.

- It ended with the intraday high on May 2, 2011.

- The next bear market was triggered by a 20% intraday drawdown midday on October 4, 2011.

- But by the end of that same day, a new bull market in intraday S&P 500 returns was underway.

- By daily data, the post-GFC bull market lasted about eleven years.

- It ended with the end-of-day high on February 19, 2020.

- The bear market was triggered by a 20% daily drawdown on March 12, 2020, just sixteen trading days later.

- The subsequent bull market began on March 24, 2020, just eight trading days after that.

- By monthly data, the post-GFC bull market lasted almost thirteen years.

- It ended with the end-of-month high on December 31, 2021.

- The bear market was triggered by a 20% monthly drawdown on September 30, 2022.

- We don’t yet know when the new monthly bull market commences.

Now TIPS are Inverted Too

In “Whence the Yield Curve Inversion” on July 20th, we noted that the substantially different shape of the real and nominal Treasury curves implied that the market’s expectations for future inflation (as observed via “break-even inflation rates”) was high in the near term but fell off quite sharply.

A couple months later, both the nominal Treasury curve and the TIPS curve are inverted, largely due to a significant moderation in near-term breakeven inflation rates, even as nominal rates continued to rise:

https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financing-the-government/interest-rate-statistics

and Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/market-data/bonds/tips (data); Explanation for the word “Kludgy” in this article: https://rtinvestments.com/insights-blog/inflation-is-up-but-the-cost-of-inflation-protected-income-is-down/

But What Does It All Mean?

We’ll dip our toe into speculative interpretation:

If you’ll recall from the yield curve inversion article, we declined at the time to address the oft-cited proposal that inversions presage economic recessions. It remains a debatable point in general, but here’s how you might (emphasis on might! market pricing doesn’t come with explanatory liner notes!) tell that story in this case:

- Significant rate hike action is required by the Federal Reserve to combat high inflation. (Clearly this part is a true story—or at the very least, the Fed itself thinks so—about which only the degree and the full timeline are uncertain.)

- Rate hikes fight inflation by reducing demand. But reduced demand also slows the economy.

- There may (emphasis on may! even if the markets really are telling this story, they can’t predict the future with certainty!) be no way to prevent this slowdown from tumbling into a recession.

Let’s provisionally go with that…

How Does This Help Me Time the Markets?

It doesn’t.

You knew we were going to say that, but here’s an explanation: Suppose the yield curve inversion means the market really is saying a recession is coming. Recessions are bad for profits, so they’re bad for stocks, right? So that means you should get out of the stock market?

Um…if the market is telling us through bond prices that a recession is coming (still just an “if”! remember the “provisionally”!), might it also, just maybe, stand to reason that that view has already been incorporated into the stock market as well? Which might look like…I dunno…the greater than 20% decline that has already taken place?!

But for that matter, there’s another plausible explanation for the equity decline. Treasury rates have skyrocketed. By definition, the “risk-free rate” is higher. To the extent expected returns for stocks are equal to the risk-free rate plus a premium, equity expected returns would need to go higher as well. And the way to get higher expected return without changing the future? Lower equity prices today.

Which of these is correct—an uglier future or a higher expected return? It could be both, in unknown proportions, with an unknown projected recession combining with an unknown risk premium to produce an unknown, but surely positive, expected return. The only component there that is known? The expected return is surely positive. But as we’ve mentioned before:

- The stock market is always priced for positive expected return, indeed for a substantially higher return than can be expected from less risky securities, such as bonds.

- The higher expected return is compensation for ever-present risk, such that it is always possible for stocks to underperform or even lose value instead.

Always remember that the market is forward-looking, and it incorporates into today’s prices all available information, including collective estimates about future economic conditions. To beat the market, it isn’t good enough to have a plausible prediction about the future. We would need a better prediction than the estimates assembled by the collective efforts of tens or hundreds of thousands of analysts, algorithms, and experts who collectively constitute the market.[1] Granted, the market turns out to be at least somewhat wrong in magnitude or direction all the time, but believing we can know in advance how the market is wrong is a mighty bold claim.

Okay, So What Can I Do?

A plausible strategy suggests itself in the bond market, at any rate. Rather than predicting the future direction of interest rates—the similarly perilous bond market equivalent to stock market timing—it is theoretically possible to extract useful intel from the expected return information already embedded in interest rates.[2] Specifically:

- Short-term interest rates are higher than long-term rates, which represents a directly higher component of expected return.

- The inverted curve may imply a negative expected roll yield as longer-term bonds become shorter-term bonds.

Based on these observations, if an investor doesn’t have other reasons to target specific maturities—and such reasons do exist!—it might make sense at present to tilt a fixed income portfolio toward shorter maturities. In fact, Round Table’s fixed income portfolios include allocations to managers who make “factor-based” decisions just like these.

Our more general suggestion is also more evergreen: Rather than tactically modifying portfolios in the hope of anticipating future market conditions, we recommend, where possible, seeking to strategically match the risk/return characteristics of investor portfolios to the investors’ personal financial goals. We’d be happy to discuss what that might look like for you!

[1] See the embedded video at the bottom of Round Table’s Investment Management page for an excellent explanation of this concept by Prof. Ken French.

[2] The discussion in this section derives from a large body of academic research, stretching back to Nobel laureate Prof. Gene Fama’s seminal paper, The information in the term structure, in the Journal of Financial Economics (Volume 13, Issue 4, December 1984)

DISCLOSURES: All content is provided solely for informational purposes and should not be considered an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Round Table Investment Strategies (Round Table) does not offer specific investment recommendations in this presentation. This article should not be considered a comprehensive review or analysis of the topics discussed in the article. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Despite efforts to be accurate and current, this article may contain out-of-date information, Round Table will not be under an obligation to advise of any subsequent changes related to the topics discussed in this article. Round Table is not an attorney or accountant and does not provide legal, tax or accounting advice. This article is impersonal and does not take into account individual circumstances. Reading this article does not create a client relationship with Round Table. An individual should not make personal financial or investment decisions based solely upon this article. This article is not a substitute for or the same as a consultation with an investment adviser in a one-on-one context whereby all the facts of the individual’s situation can be considered in their entirety and the investment adviser can provide individualized investment advice or a customized financial plan.

The data shown in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as an investment recommendation or strategy, or as an offer to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. While the sources of data included in any charts/graphs/calculations are believed to be reliable, Round Table cannot guarantee their accuracy.