[UPDATE, 5/15/2023: This article is now available on Advisor Perspectives! — www.advisorperspectives.com/articles/2023/05/15/does-it-still-make-sense-to-buy-i-bonds-dutzmann]

I-Bonds: That was Then

Nearly a year ago, we—provisionally and with qualifications—declared Series I Savings Bonds (“I-Bonds”) to be the fabled “free lunch” due to the remarkable, government-guaranteed 9.62% annualized interest rate that they were then paying, at a time when most savings accounts were still offering a paltry fraction of one percent. (Note: For a refresher on I-Bond basics, see our initial article on the topic.)

Since I-Bonds are inflation-linked instruments, that interest rate was driven by multi-decade highs for inflation rates. So really, the fact that I-Bond rates have now come back down to earth is probably more good than bad.

I-Bonds: This is Now

The new headline rate, beginning here in May 2023, is 4.30%. However, even that level includes a 0.90% fixed rate for bonds purchased between May and October of this year. I-Bonds purchased previously will pay an even lower rate. Any I-Bonds purchased prior to last November (which would include any that were obtained in time to snag that snazzy 9.62% rate) carry a 0% fixed rate, so they will pay just the inflation rate of 3.38%.[1]

Meanwhile, many other safe options, such as Treasury Bills and CDs, are now paying interest rates of 4.5% or more. So what should we do with our I-Bonds now? Of course, one option would be to give Round Table a jingle, so we can construct a personalized recommendation for you. Barring that, though, this article offers some general thoughts.

A Kenny Rogers Framework for I-Bond Decisions

And what better way to organize those thoughts than with a country song? While it seems Kenny Rogers discovered profound life lessons in what “The Gambler” told him, I’ve long harbored a suspicion the old codger was just trying to convince Kenny to dig out of his debts with a few lucky hands of poker.

Nonetheless, now that the free lunch buffet is closed, the gambler’s pithy adages can help us sift through a few viable approaches to I-Bonds…even if I-Bonds are about as far from gambling as you can get.

Know When to Hold ‘Em

When I-Bonds were introduced in the late ‘90s, the idea was certainly not to offer the public a short-term trading instrument. While the short-term tactical maneuver (a.k.a., the free lunch) that arose last year caused popular interest in the instruments to explode, the primary use case for I-Bonds is the same as it always was: I-Bonds are a secure, non-volatile, (short- and) long-term inflation hedge.

A couple examples of this use case would be:

- Holding I-Bonds as an inflation-adjusted savings account or emergency fund.[2]

- Buying more I-Bonds every year, to build up an inflation-adjusted nest egg, e.g., for retirement.[3]

If this strategic approach is someone’s primary rationale for holding I-Bonds, then they should carry on, by all means! Yes, the inflation-linked interest feature of I-Bonds will sometimes produce a lower interest rate than is available elsewhere, but most of those elsewheres don’t offer an ongoing, guaranteed inflation hedge.

Know When to Fold ‘Em

On the flipside, there’s no mystery about why I-Bonds became so popular of late. While I-Bonds were not developed to be shortish-term,[4] tactical trading tools, that is absolutely a viable use for them anyway, and the arbitrage they offered last year was upwards of historic.

With that window now closed, it isn’t crazy to sell out of I-Bonds and pursue something else with your fun money. But timing is important, and, well, I-Bonds are a government program, which means everything about them is more complicated than it likely needed to be.

For example, if you’ve held your I-Bonds for less than five years—and c’mon, how many of us have I-Bonds older than that?—then upon redemption, you will forfeit the last three months of accrued interest. (If you’ve held your I-Bonds for less than one year, you won’t be allowed to redeem them yet at all.) Consequently, you gotta…

Know When to Walk Away

If three months’ worth of interest are to be given up, then they might as well be three months of lower interest. But that would mean waiting for three months at the new 3.38% inflation rate before redeeming, so as not to lop off any accruals at the old 6.48% rate.

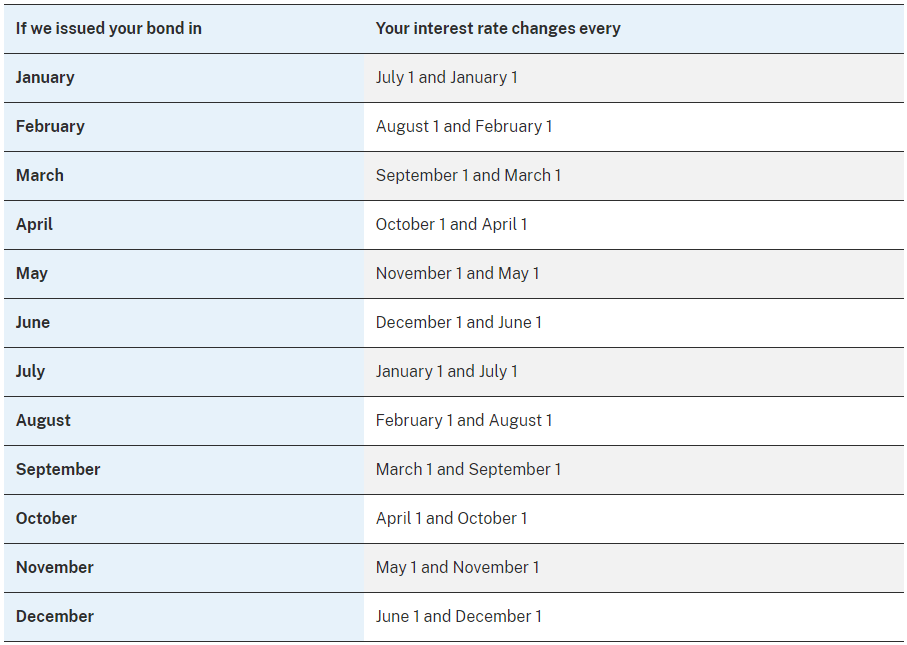

But it’s more complicated than just waiting three months from here! Now that it’s May, the new, lower I-Bond rate has been introduced. But that doesn’t necessarily mean your I-Bonds are already accruing that lower rate. Recall that when you buy an I-Bond, you lock in the then-current interest rate for six months, which starts a six-monthly cycle unique to your purchase month (and the one six months before/after).

Consequently, previously purchased I-Bonds are only starting to accrue the new rate in May if they were bought in either May or November. I-Bonds originally acquired in other calendar months are still accruing the 6%+ rate for at least this month. Here is a handy-dandy table from the TreasuryDirect site showing when the new interest rate will begin for bonds purchased in any given month:

So, for example, I-Bonds purchased in the month of December will start accruing the 3.38% rate in June. It might be sensible to wait until September to redeem them, so that the three months of relinquished interest (June/July/August) are at the lower rate. For I-Bonds purchased in, say, the month of April, the new rate doesn’t kick in until October, so it might make sense to wait to redeem until January![5]

Know When to Run (Um…in circles? Right back to I-Bonds?)[6]

So much for the tactical I-Bond traders. But folks in the long-term-hold camp may have an interesting option as well. If the plan is to keep buying I-Bonds each year, then carry on, nothing to see here. But if you’re happy with your current quantity, then The Gambler might suggest you swap out some of your cards.

Here’s the rationale: Any I-Bonds you bought before last November (but after November 2019) are accruing a 0% fixed rate, which is locked in for the life of the bond. If you sell $10,000 per person of those bonds, you will give up three months of accrued interest, but then if you buy back $10,000 per person of new I-Bonds, you will lock in a 0.9% fixed rate. The permanence of the extra 0.9% means you will ultimately come out ahead, likely within a little over a year, before taxes.[7] (Note that you will owe taxes on earned interest upon redemption.)

But, doggone it, even this may be complicated. Consider, from above, I-Bonds purchased in the month of April. You’d need to wait until January to sell them, to avoid losing any months at the 6.48% rate. But the 0.9% fixed rate is only in effect for bonds purchased now through October!

Three options for resolving this conundrum present themselves:

- Folks who have the extra money sitting around and can afford to float themselves a couple months could buy the new I-Bonds in October and sell the old ones in January.

- You could do the swaperoo in October and live with losing a few months at 6.48% instead. This would approximately double the expected time to break even.

- You could play The Gambler yourself and wait to see what the fixed rate introduced in November looks like. After all, it could go even higher!

Granted, 0.90% is the highest fixed rate for I-Bonds in over 15 years, but that’s because interest rates overall have been so low for so long. My best guess: If TIPS rates don’t decline between now and November, then fixed rates for I-Bonds likely won’t either.[8]

Be aware that any dollars with which you perform this prestidigitation will be locked in for 12 months. The five-year calendar for giving up interest accruals will reset on those dollars as well.

You Never Count Your…Wait, forget it, you do have to count your own money when you’re sitting at the I-Bond table

As we’re pondering all of the above, it might be nice to know exactly how much accrued interest we’d be giving up if we choose to redeem our I-Bonds. Unfortunately, the TreasuryDirect website doesn’t tell us.

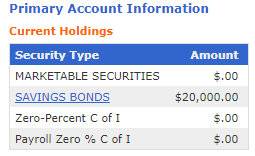

For example, if I log into my account, here’s what my landing page says:

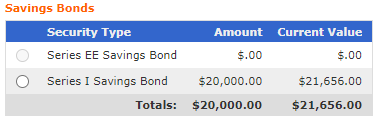

The $20,000 figure in that table is how much I purchased originally, over two calendar years. It is emphatically not what my I-Bonds are worth now![9] If I click on that “SAVINGS BONDS”[10] hyperlink, I get a page with this table:

Unfortunately, that “Current Value” is also not what my I-Bonds are worth now, if “worth now” is taken to mean “inclusive of all interest accrued thus far.” Rather, the “Current Value” shows only the amount that would be available upon redemption, net of forgoing the last three months of accrued interest. It isn’t a completely worthless figure, but it leaves open the question of exactly how much accrued interest would be thusly forwent.

I hereby promote to body text a portion of a footnote from a prior article:

I emailed the folks at TreasuryDirect to ask why they don’t also show the total accrued interest, and their response was, and I quote, “It would be too confusing for most people to see this full amount…” Yup, right, we don’t want to confuse people.

Sigh…

To get the full picture, we have to do the calculation ourselves. Thankfully, there are a couple tools available:

- TreasuryDirect itself offers a calculator that it claims is for paper savings bonds, but it works fine for electronic bonds as well: https://www.treasurydirect.gov/BC/SBCPrice

- There are several tricky bits to this. (Of course there are!) Here’s an article by David Enna, who runs the fabulous TIPS Watch website, with a step-by-step guide on how to get the info you want.

- Alternatively, the eyebonds.info website offers a calculator from which you can select the amount and date of purchase and see current, past, and future accrued value: http://eyebonds.info/ibonds/index.html

- Note that you have to do this separately for each date on which I-Bonds were purchased.

When I run these calculations for my I-Bonds, I learn that my total accrued value comes to $22,060, which means I would give up $404 ($22,060 – $21,656) of accrued interest if I redeemed all my I-Bonds today.

There’ll be Time Enough for Countin’ when the Dealing’s Done

I’m done dealing. Feel free to get countin’!

[1] Anyone bothering to do the math, or even just looking at the final decimal places, will have noticed that 0.90% plus 3.38% does not equal 4.30%. This is because the Treasury, invoking the axiom that nothing about I-Bonds is allowed to be simple, uses the following formula for calculating the composite I-Bond rate:

Composite Rate = Fixed Rate + (2 x Semiannual Inflation Rate) + (Fixed Rate x Semiannual Inflation Rate)

Here’s what that looks like right now:

Composite Rate = 0.90% + (2 x 1.69%) + (0.90% x 1.69%) = 0.90% + 3.38% + 0.02% = 4.30%

If there is a theoretical rationale, beyond the aforementioned Axiom of Ubiquitous Confusion, for the seemingly superfluous “(Fixed Rate x Semiannual Inflation Rate)” term that creates the extra 0.02% interest, I am at present unaware of it.

[2] This is how I use them myself.

[3] Given the $10,000/person/year purchase limits, this strategy may be most workable if you start relatively young. Then again: (A) I-Bonds automatically mature after 30 years, so they won’t continue accruing inflation-adjusted interest throughout a young person’s future retirement; (B) considerations of human capital and risk capacity raise questions about the validity of acquiring instruments so low on the risk/reward scale early in one’s career. At Round Table, we solve both issues with a system that glides into a TIPS portfolio for secure, inflation-protected retirement income.

[4] The minimum one-year holding period for I-Bonds demands the “ish.”

[5] And this is because of accruals driven by inflation calculations that started last November! We discussed this wild I-Bond lag at some length previously.

[6] Give me a break, I can’t make it all fit perfectly!

[7] Various articles on the interwebs have mistakenly assumed a simple calculation exists for this sort of breakeven analysis. Due to differences in accrual timing and uncertainties about future rates—and of course the Axiom of Ubiquitous Confusion—no such simple calculation exists. But pulling ahead is very likely within two years and quite possible within one year for someone who sacrifices three months at 3.38% to capture an extra 0.9% fixed in perpetuity. (The extra basis points introduced by the Axiom of Ubiquitous Confusion in footnote 1 help as well.)

[8] For a 5,000-word explanatory background for this 17-word sentence, see this previous article: https://rtinvestments.com/insights-blog/i-bonds-vs-tips-compare-and-contrast/

[9] In fact, my account has never been worth exactly $20,000, since I had accrued some interest on the original $10,000 before I could purchase the other $10,000.

[10] Why they shout this at us is unclear.

Gambler image created by Fotor AI image generator.

DISCLOSURES: All content is provided solely for informational purposes and should not be considered an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Round Table Investment Strategies (Round Table) does not offer specific investment recommendations in this presentation. This article should not be considered a comprehensive review or analysis of the topics discussed in the article. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Despite efforts to be accurate and current, this article may contain out-of-date information; Round Table will not be under an obligation to advise of any subsequent changes related to the topics discussed in this article. Round Table is not an attorney or accountant and does not provide legal, tax or accounting advice. This article is impersonal and does not take into account individual circumstances. An individual should not make personal financial or investment decisions based solely upon this article. This article is not a substitute for or the same as a consultation with an investment adviser in a one-on-one context whereby all the facts of the individual’s situation can be considered in their entirety and the investment adviser can provide individualized investment advice or a customized financial plan.

The data shown in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as an investment recommendation or strategy, or as an offer to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. While the sources of data included in any charts/graphs/calculations are believed to be reliable, Round Table cannot guarantee their accuracy.