For those of us who subscribe to the notion that the market displays even a modicum of efficiency[1] in the pricing of stocks, the following two principles are corollaries:

- The stock market is always priced for positive expected return, indeed for a substantially higher return than can be expected from less risky securities, such as bonds.

- The higher expected return is compensation for ever-present risk, such that it is always possible for stocks to underperform or even lose value instead.

The word expected in “expected return” refers to the average of all possible future outcomes. An efficient (or even remotely close to efficient) market will incorporate all available information into current stock prices such that the expected return premium is significantly positive. Consequently, Round Table, like most investment advisors, will generally recommend that investors hold equities[2] in their portfolios, in proportions concomitant with their risk capacity and risk tolerance, insofar as doing so fits their overall financial plan.

Yet with the passage of time, as new information arrives, the market will update its expectations for the future state of the economy, future corporate profits, etc. This process can cause stock prices to go up or down. If the adjustment is large enough, it can even drive equities into a “bear market,” which is informally but almost universally defined as a decline of 20% from previous all-time highs. When a bear market is in full swing, it’s only natural for investors to wonder…

“What Should I Do Now?”

Our answer goes back to first principles. When an examination of someone’s holistic financial picture first led them to invest in equities, presumably the following were all true:[3]

- The higher expected return of stocks was worth pursuing, the riskiness of stocks notwithstanding.

- They had the capacity to take equity risk, in exchange for the potential to capture that higher expected return. (I.e., for a variety of possible reasons, they could “afford” the risk.)

- Holding stocks in their portfolio was a sensible element of their overall financial plan.

When the market is down 20% or more, it’s easy to get caught up in the emotional challenges of watching portfolio values decline. But if investors can zoom out to a birds-eye view of their overall financial plan, most would probably find:

- The higher expected return of stocks is still worth pursuing, the riskiness of stocks notwithstanding.

- They still have the capacity to take equity risk, in exchange for the potential to capture that higher expected return.[4]

- Holding stocks in their portfolio is still a sensible element of their overall financial plan.

More succinctly, we believe the decision to invest in equities should be made strategically, as part of an overall plan. And as the markets fluctuate, we encourage investors to continue thinking strategically rather than tactically.

Historical Evidence for Strategic Thinking

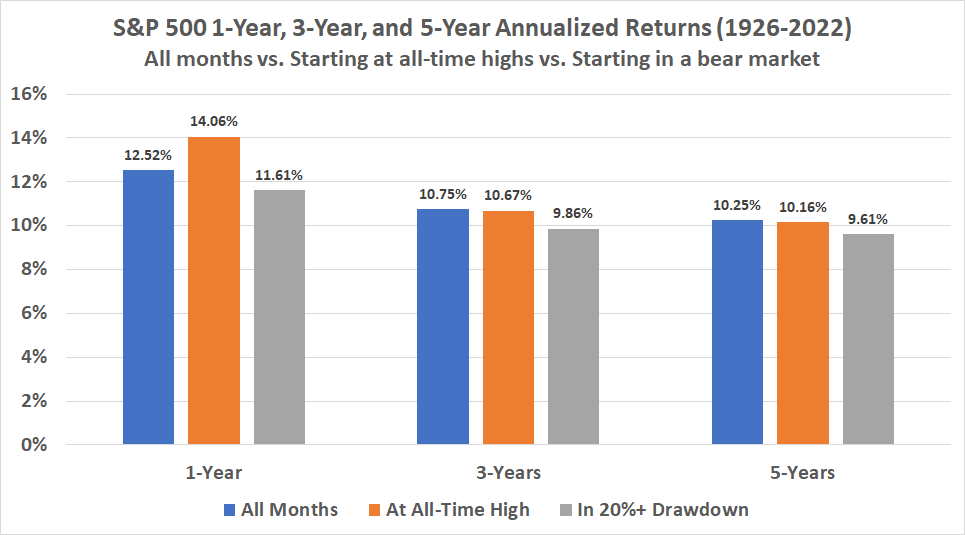

As discussed on our Investment Management page, at Round Table we believe trying to “time” the stock market by jumping in and out of your investments is a potentially expensive and likely futile endeavor. This includes panic-selling in a bear market. As evidence, consider the following chart, which shows the average annualized one-year,[5] three-year, and five-year returns of the S&P 500 Index from January 1926 through April 2022, following each month-end that falls into any of three buckets:

- All months. I.e., what is the average return of all 1/3/5-year periods for the S&P 500?

- Starting at all-time highs. I.e., how did the index perform 1/3/5 years after hitting an all-time monthly high?

- Starting in a bear market. I.e., how did the index perform 1/3/5 years after a month-end in which it was in a drawdown of 20% or greater?

(Uses monthly S&P 500 total returns, January 1926 through April 2022.)

The primary lesson of this chart is a simple one: After strong stock market performance, after weak stock market performance, or indeed after all kinds of performance, the average return of the market has been very strong. Some investors fear that a stock market at all-time highs must be due for a fall. The chart above suggests otherwise. Other investors are tempted to pull the ripcord when the market has declined substantially. The chart above suggests the opportunity cost of doing so may be substantial.

No outcomes are guaranteed, of course. For example, the annualized 5-year returns of the S&P 500 range from +36% to -17% historically, and the 5-year returns starting from a 20%+ drawdown range from +36% to -13% annualized. The two basic principles at the beginning of this article always apply.

Granted, the above chart indicates that the historical average 1-, 3-, and 5-year return of the S&P 500 following bear market performance has been slightly lower than the overall average, but two observations blunt the impact of this observation:

- While, for example, the 9.61% annualized 5-year return is lower than 10.25%, it still represents considerably better average performance than could be obtained on average from bonds or other less-risky investments. So even if a bear market did imply slightly lower-than-average expected returns, that alone would not be sufficient reason to stop investing.

- The average underperformance is driven entirely by the outsized drawdowns that occurred during the Great Depression. Since 1940, the average 1-year (14.14% vs. 12.81%), 3-year (13.95% vs. 11.96%), and 5-year (12.24% vs. 11.72%) returns have been somewhat higher when starting from a 20%+ drawdown. We don’t recommend throwing out an outlier like the Great Depression, but it is worth noting when a single outlier has such a large effect on an analysis.

Final Note

While we think these principals are broadly applicable and evergreen, they do not answer questions like exactly how much equity to hold, which investment products to purchase, and, most especially, how to tailor your investments to your specific goals and circumstances. Please feel free to reach out to us at Round Table if you’d like to dive into these personalized questions!

[1] See this link for a basic discussion of the concept of market efficiency: https://www.investopedia.com/insights/what-is-market-efficiency/

[2] The terms “stocks” and “equities” are used interchangeably in this discussion.

[3] Of course, if any of these were not true, the decision to invest in stocks (or perhaps the magnitude of the investment) may have been in error. Round Table Investment Strategies specializes in crafting portfolios that are individually tailored to our clients’ goals, needs, and financial circumstances. Please feel free to reach out if you would like to have a strategic investment discussion with us.

[4] Granted, the precise amount of equity an investor has the capacity to hold may have changed somewhat. Also, the amount of equity the investor actually holds has likely declined with the markets. There is much, much more that can be said about how to determine the right amount of stock exposure in a portfolio. For example, see Round Table’s “Layer Cake” retirement investment methodology. For a discussion personalized to your circumstances, please reach out to us any time!

[5] Wonky quiz question for the numerically inclined: In the return chart, why are the average one-year returns so much higher than the average annualized three- and five-year returns, even in the “all months” series where we’re looking at the same index over the same long-term timeframe? Hint here: https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/06/geometricmean.asp

DISCLOSURES: All content is provided solely for informational purposes and should not be considered an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Round Table Investment Strategies (Round Table) does not offer specific investment recommendations in this presentation. This article should not be considered a comprehensive review or analysis of the topics discussed in the article. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Despite efforts to be accurate and current, this article may contain out-of-date information; Round Table will not be under an obligation to advise of any subsequent changes related to the topics discussed in this article. Round Table is not an attorney or accountant and does not provide legal, tax or accounting advice. This article is impersonal and does not take into account individual circumstances. An individual should not make personal financial or investment decisions based solely upon this article. This article is not a substitute for or the same as a consultation with an investment adviser in a one-on-one context whereby all the facts of the individual’s situation can be considered in their entirety and the investment adviser can provide individualized investment advice or a customized financial plan.

The data shown in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as an investment recommendation or strategy, or as an offer to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. While the sources of data included in any charts/graphs/calculations are believed to be reliable, Round Table cannot guarantee their accuracy.